Transforming Supports in a Trauma-Sensitive Environment

At Dungarvin Connecticut, we are transforming to apply clinical supports in a trauma-sensitive environment.

I sit quietly in the waiting room. Waiting always waiting; waiting on staff, waiting on my housemates, waiting to eat, waiting to take my meds, waiting for my ride, waiting for my appointment. Ugh! I rattle in my brain. I always was waiting. Over and over again all growing up, I waited and no one came home. I waited to eat. But, no one fed me. I waited in the dark. I heard the footsteps outside my door. But again, he came in and not my mom. Ugh! I can’t think about that. I can’t stand waiting. Why do they do this to me? Always have to wait; I can’t go, I can’t stay; I feel heat run through my body. I have to scream. I can’t. I ask my staff if we can leave. She says we have to wait. I rage. I go for her face. Punching, scratching. I can’t stop myself!

I am back in the chair; breathing heavily. Staff pin my arms against the chair. I can’t get up. I can’t move. She tells me to calm down and breathe. I can’t breathe. She keeps talking to me. I find it soothing. I can breathe. I am so sorry for scratching her.

The doctor will see me now. I hear the report about how aggressive I am. More meds ordered. Ugh. I am invisible. How long will I have to wait for someone to see me?

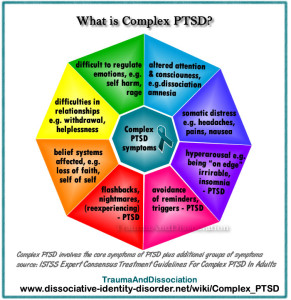

The National Child Trauma Stress Network defines the term complex trauma as “the problem of children’s exposure to multiple or prolonged traumatic events and the impact of this exposure on their development.” It may include neglect, physical and sexual abuse, domestic violence, and psychological abuse; it is chronic, begins in early childhood, and occurs within the primary care giving system. It can also begin prenatally with physical abuse to the pregnant mother, drug or alcohol abuse, and excessive cortisol production in response to significant and chronic stress that can negatively impact fetal development.

Only recently has the community of clinical practitioners considered those with intellectual disabilities appropriate candidates for counseling and other forms of psychotherapy, especially those with complex trauma. Challenging behaviors and demonstrations of emotional dis-regulation, previously regarded to function as “attention-seeking” or “task avoidance”, are now more widely recognized as signs and symptoms of emotional grief, mental health disorders, and trauma. Examples of such behaviors include self-abuse, aggression, property destruction, elopement, disrupted sleep; startle reflex, hyper-vigilance, refusals to engage in even pleasurable activities.

SAMSHA, in 2011, stated that an overwhelming percentage of the population has suffered “adverse events” that can be considered traumatic. According to Denise Valenti-Heim’s decades of clinical work and research, more than 90% of people with intellectual disabilities will experience some form of sexual abuse at some time in their lives. 49% will experience 10 or more abusive incidents.

To meet the needs and skills of those with intellectual disabilities who have survived trauma, some clinicians have adapted formal therapy models that are commonly employed to treat trauma, such as cognitive-behavior therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), solution-focused brief therapy, symbolic interactive therapy, systematic desensitization, to name a few. These clinicians are exploring deeper layers of the psychological experience in an effort to address the illness and/or trauma; to provide the opportunity for actual healing. They transform the traditional model through a 6-point process to assist the individual learn, grow and develop the skills to handle stress, negotiate conflict, and attract and enjoy healthy relationships.

- Treat mental health issues through psycho-education about how the trauma impacted their sense of identity and worth, their rights to be safe, what is socially acceptable behavior, what is a healthy relationship, and how to effectively express feelings, needs, and preferences; develop self-confidence and positive self-image, and through psychopharmacology as necessary

- Address medical problems

- Minimize harm through trauma-sensitive programming and support

- Transform support system

- Educate the people in the individual’s life to minimize harm and PTSD triggers

- Participate in counseling

At Dungarvin Connecticut, we have embraced the transformation and recently opened our first home with a support system specifically focused on providing a trauma-sensitive healing environment in one of our CRS homes. This involved specific education and training, a redesign of behavior supports and IP development, and a paradigm shift in our perspective and approach to providing those supports.

Our team participated in a 2-day, complex trauma training, facilitated by the individual’s clinician, specifically focused on the individual the staff were to support. This was preceded by a 2-day, introduction to intellectual disabilities, mental health disorders, Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) training, and teaching strategies.

Learning to identify feelings and express them effectively is a focus of this individual’s recovery because her challenges with these skills, has previously resulted in significant aggression, self-abusive behavior and elopement (as it is with many who have experienced trauma). While she participates in therapy with the clinician twice a week, one of the sessions takes place in her home (our program) to provide her the assistance she needs to apply what she learns in her office-based session. It is an opportunity for her to effectively express her needs, feelings, and preferences with both the staff and clinician present. With the support and guidance from the clinician, the individual is learning to tolerate increasing amounts of stress, work through misunderstandings, and self-advocate rather than self-destruct. Her first act of self advocacy was to request a change from the term, “staff”. She redefined our roles; we are “managers” or “workers” rather than “staff” as we are helping her to manage her life and we are working to support her.

This program is in its infancy and there is much more to learn from the experts and from the people we support in order to truly transform our support systems. We are dedicated to respecting and responding to the choices (and needs) of those we support; and are willing to do the work necessary to assist people with intellectual disabilities live with dignity and joy for as long as they will allow us to.

Add A Comment